By lbackstrom - Topcoder Member

Discuss this article in the forums

Introduction

Vectors

Vector Addition

Dot Product

Cross Product

Line-Point Distance

Polygon Area

Introduction

Many topcoders seem to be mortally afraid of geometry problems. I think it’s safe to say that the majority of them would be in favor of a ban on topcoder geometry problems. However, geometry is a very important part of most graphics programs, especially computer games, and geometry problems are here to stay. In this article, I’ll try to take a bit of the edge off of them, and introduce some concepts that should make geometry problems a little less frightening.

Vectors

Vectors are the basis of a lot of methods for solving geometry problems. Formally, a vector is defined by a direction and a magnitude. In the case of two-dimension geometry, a vector can be represented as pair of numbers, x and y, which gives both a direction and a magnitude. For example, the line segment from (1,3) to (5,1) can be represented by the vector (4,-2). It’s important to understand, however, that the vector defines only the direction and magnitude of the segment in this case, and does not define the starting or ending locations of the vector.

Vector Addition

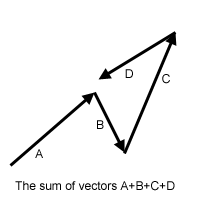

There are a number of mathematical operations that can be performed on vectors. The simplest of these is addition: you can add two vectors together and the result is a new vector. If you have two vectors (x1, y1) and (x2, y2), then the sum of the two vectors is simply (x1+x2, y1+y2). The image below shows the sum of four vectors. Note that it doesn’t matter which order you add them up in – just like regular addition. Throughout these articles, we will use plus and minus signs to denote vector addition and subtraction, where each is simply the piecewise addition or subtraction of the components of the vector.

Dot Product

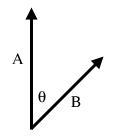

The addition of vectors is relatively intuitive; a couple of less obvious vector operations are dot and cross products. The dot product of two vectors is simply the sum of the products of the corresponding elements. For example, the dot product of (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) is x1*x2 + y1*y2. Note that this is not a vector, but is simply a single number (called a scalar). The reason this is useful is that the dot product, A ⋅ B = |A||B|Cos(θ), where θ is the angle between the A and B. |A| is called the norm of the vector, and in a 2-D geometry problem is simply the length of the vector, sqrt(x2+y2). Therefore, we can calculate Cos(θ) = (A ⋅ B)/(|A||B|). By using the acos function, we can then find θ. It is useful to recall that Cos(90) = 0 and Cos(0) = 1, as this tells you that a dot product of 0 indicates two perpendicular lines, and that the dot product is greatest when the lines are parallel. A final note about dot products is that they are not limited to 2-D geometry. We can take dot products of vectors with any number of elements, and the above equality still holds.

Cross Product

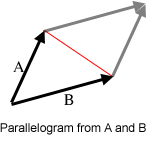

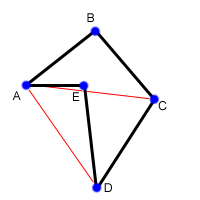

An even more useful operation is the cross product. The cross product of two 2-D vectors is x1*y2 - y1*x2 Technically, the cross product is actually a vector, and has the magnitude given above, and is directed in the +z direction. Since we’re only working with 2-D geometry for now, we’ll ignore this fact, and use it like a scalar. Similar to the dot product, A x B = |A||B|Sin(θ). However, θ has a slightly different meaning in this case: |θ| is the angle between the two vectors, but θ is negative or positive based on the right-hand rule. In 2-D geometry this means that if A is less than 180 degrees clockwise from B, the value is positive. Another useful fact related to the cross product is that the absolute value of |A||B|Sin(θ) is equal to the area of the parallelogram with two of its sides formed by A and B. Furthermore, the triangle formed by A, B and the red line in the diagram has half of the area of the parallelogram, so we can calculate its area from the cross product also.

Line-Point Distance

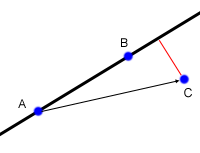

Finding the distance from a point to a line is something that comes up often in geometry problems. Lets say that you are given 3 points, A, B, and C, and you want to find the distance from the point C to the line defined by A and B (recall that a line extends infinitely in either direction). The first step is to find the two vectors from A to B (AB) and from A to C (AC). Now, take the cross product AB x AC, and divide by |AB|. This gives you the distance (denoted by the red line) as (AB x AC)/|AB|. The reason this works comes from some basic high school level geometry. The area of a triangle is found as base*height/2. Now, the area of the triangle formed by A, B and C is given by (AB x AC)/2. The base of the triangle is formed by AB, and the height of the triangle is the distance from the line to C. Therefore, what we have done is to find twice the area of the triangle using the cross product, and then divided by the length of the base. As always with cross products, the value may be negative, in which case the distance is the absolute value.

Things get a little bit trickier if we want to find the distance from a line segment to a point. In this case, the nearest point might be one of the endpoints of the segment, rather than the closest point on the line. In the diagram above, for example, the closest point to C on the line defined by A and B is not on the segment AB, so the point closest to C is B. While there are a few different ways to check for this special case, one way is to apply the dot product. First, check to see if the nearest point on the line AB is beyond B (as in the example above) by taking AB ⋅ BC. If this value is greater than 0, it means that the angle between AB and BC is between -90 and 90, exclusive, and therefore the nearest point on the segment AB will be B. Similarly, if BA ⋅ AC is greater than 0, the nearest point is A. If both dot products are negative, then the nearest point to C is somewhere along the segment. (There is another way to do this, which I’ll discuss here).

//Compute the dot product AB ⋅ BC

int dot(int[] A, int[] B, int[] C){

AB = new int[2];

BC = new int[2];

AB[0] = B[0]-A[0];

AB[1] = B[1]-A[1];

BC[0] = C[0]-B[0];

BC[1] = C[1]-B[1];

int dot = AB[0] * BC[0] + AB[1] * BC[1];

return dot;

}

//Compute the cross product AB x AC

int cross(int[] A, int[] B, int[] C){

AB = new int[2];

AC = new int[2];

AB[0] = B[0]-A[0];

AB[1] = B[1]-A[1];

AC[0] = C[0]-A[0];

AC[1] = C[1]-A[1];

int cross = AB[0] * AC[1] - AB[1] * AC[0];

return cross;

}

//Compute the distance from A to B

double distance(int[] A, int[] B){

int d1 = A[0] - B[0];

int d2 = A[1] - B[1];

return sqrt(d1d1+d2d2);

}

//Compute the distance from AB to C

//if isSegment is true, AB is a segment, not a line.

double linePointDist(int[] A, int[] B, int[] C, boolean isSegment){

double dist = cross(A,B,C) / distance(A,B);

if(isSegment){

int dot1 = dot(A,B,C);

if(dot1 > 0)return distance(B,C);

int dot2 = dot(B,A,C);

if(dot2 > 0)return distance(A,C);

}

return abs(dist);

}

That probably seems like a lot of code, but lets see the same thing with a point class and some operator overloading in C++ or C#. The * operator is the dot product, while ^ is cross product, while + and – do what you would expect.

//Compute the distance from AB to C

//if isSegment is true, AB is a segment, not a line.

double linePointDist(point A, point B, point C, bool isSegment){

double dist = ((B-A)^(C-A)) / sqrt((B-A)(B-A));

if(isSegment){

int dot1 = (C-B)(B-A);

if(dot1 > 0)return sqrt((B-C)(B-C));

int dot2 = (C-A)(A-B);

if(dot2 > 0)return sqrt((A-C)*(A-C));

}

return abs(dist);

}

Operator overloading is beyond the scope of this article, but I suggest that you look up how to do it if you are a C# or C++ coder, and write your own 2-D point class with some handy operator overloading. It will make a lot of geometry problems a lot simpler.

Polygon Area

Another common task is to find the area of a polygon, given the points around its perimeter. Consider the non-convex polygon below, with 5 points. To find its area we are going to start by triangulating it. That is, we are going to divide it up into a number of triangles. In this polygon, the triangles are ABC, ACD, and ADE. But wait, you protest, not all of those triangles are part of the polygon! We are going to take advantage of the signed area given by the cross product, which will make everything work out nicely. First, we’ll take the cross product of AB x AC to find the area of ABC. This will give us a negative value, because of the way in which A, B and C are oriented. However, we’re still going to add this to our sum, as a negative number. Similarly, we will take the cross product AC x AD to find the area of triangle ACD, and we will again get a negative number. Finally, we will take the cross product AD x AE and since these three points are oriented in the opposite direction, we will get a positive number. Adding these three numbers (two negatives and a positive) we will end up with a negative number, so will take the absolute value, and that will be area of the polygon.

The reason this works is that the positive and negative number cancel each other out by exactly the right amount. The area of ABC and ACD ended up contributing positively to the final area, while the area of ADE contributed negatively. Looking at the original polygon, it is obvious that the area of the polygon is the area of ABCD (which is the same as ABC + ABD) minus the area of ADE. One final note, if the total area we end up with is negative, it means that the points in the polygon were given to us in clockwise order. Now, just to make this a little more concrete, lets write a little bit of code to find the area of a polygon, given the coordinates as a 2-D array, p.

int area = 0;

int N = lengthof§;

//We will triangulate the polygon

//into triangles with points p[0],p[i],p[i+1]

for(int i = 1; i+1<N; i++){

int x1 = p[i][0] - p[0][0];

int y1 = p[i][1] - p[0][1];

int x2 = p[i+1][0] - p[0][0];

int y2 = p[i+1][1] - p[0][1];

int cross = x1y2 - x2y1;

area += cross;

}

return abs(area/2);

Notice that if the coordinates are all integers, then the final area of the polygon is one half of an integer.